The Scarcity Paradox

What Pokemon Cards, Magic: The Gathering, and a Texas Landfill Reveal About Value in a World of Infinite Money

Two weeks ago, three masked men walked into a Pokemon card shop in Manhattan's Meatpacking District during a community arts-and-crafts event.

They were carrying anime backpacks. One had a hammer. Another had a handgun.

For the next three minutes, they held 40 people at gunpoint while systematically smashing display cases and stuffing graded cards into their bags. They made off with over $100,000 in merchandise—including a PSA 10 Charizard worth $23,000 alone.

The robbery at Poké Court wasn't an isolated incident. Similar heists hit card shops in Boston, Los Angeles, Seattle, and Simi Valley within the same week. In November, thieves stole nearly $10,000 worth of cards from Tom Brady's SoHo collectibles store.

Criminals are treating Pokemon cards like diamonds now.

And maybe they're onto something.

Here's a number that should stop you cold.

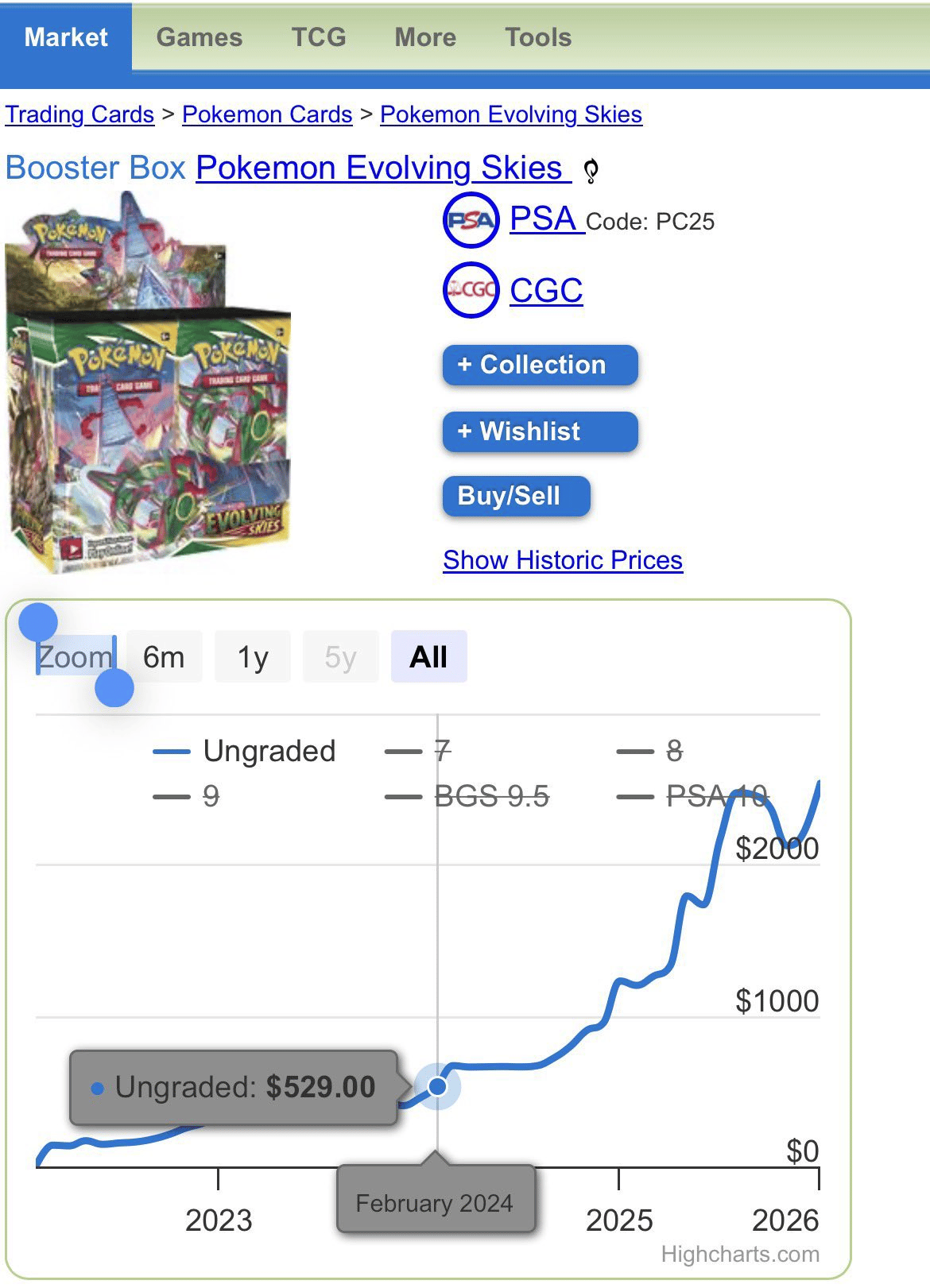

If you had invested $5,000 into sealed Pokemon Evolving Skies booster boxes two years ago—when they were trading around $525 each—your position would now be worth approximately $24,000.

That same $5,000 in gold? About $10,400.

Pokemon cardboard outperformed gold by $13,000. It also beat the S&P 500 and the Nasdaq over the same window.

The price chart for Evolving Skies looks like a rocket launch. Boxes traded sideways between $400-600 from 2021 through early 2024. Then the set went definitively out of print, remaining supply concentrated in collector hands, and the curve went vertical—past $1,000 in mid-2025, approaching $2,500 by January 2026.

The investment return? 408% over three years. One analysis projects $3,000 boxes by year-end.

The Umbreon VMAX alternate art card from that set—with a 1:1,500 pull rate—went from $100 in 2021 to $1,430 by July 2025. That's 1,330% appreciation on a piece of cardboard.

Meanwhile, at Costco, something equally strange is happening.

The warehouse retailer started selling 1-ounce gold bars in 2023 as an experiment. Within months, they were moving $100-200 million in bullion per month. Wells Fargo analysts couldn't believe the numbers.

The bars sell out within minutes of restocking. Bots track inventory and blast alerts via Telegram. People camp the website like it's a Supreme drop. By May 2025, Costco had to impose purchase limits: one transaction per membership, maximum four bars per 24 hours.

As of December 2025, a PAMP Suisse bar that sold for under $2,000 two years ago lists for $4,119.99—a 108% increase. Millennials, who now account for over 60% of gold investors according to State Street's 2024 Gold ETF Impact Study, have nearly doubled their gold allocations in just 15 months.

The demand is so intense that Costco expanded into silver coins, platinum bars, and gold eagles. The American Eagle coins sold out in 18 minutes.

Ray Dalio, founder of the world's largest hedge fund, explained the phenomenon at Abu Dhabi Finance Week: "I want to steer away from debt assets like bonds and debt, and have some hard money like gold and Bitcoin."

He cited "unprecedented levels" of indebtedness across all major economies. His conclusion: a debt crisis is mathematically inevitable.

What connects armed Pokemon heists to Costco gold frenzies?

The answer is simpler than you'd think: scarcity.

When money supply compounds at 5-7% annually—and sometimes much faster—while the supply of certain assets stays fixed or grows slowly, those assets appreciate in nominal terms almost by default. You're not necessarily getting richer. The measuring stick is getting shorter.

Since 1970, global money supply has exploded from under $1 trillion to over $100 trillion. A 100x expansion. Hard assets—things that can't be printed at will—have become the logical response.

Gold's scarcity comes from physics. Annual mine supply adds roughly 1.5% to existing above-ground stock. No human decision can change that.

Pokemon's scarcity comes from company behavior. The Pokemon Company moves on to new sets and doesn't do major reprints. The supply is the supply.

But here's the critical insight most investors miss: scarcity isn't just about how much of something exists. It's about trust that the supply constraint will hold.

And that trust can be worth billions.

Or it can be destroyed.

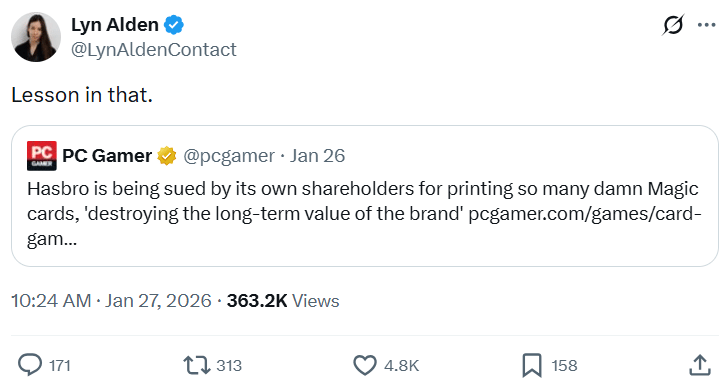

Three days ago, Hasbro—the parent company of Wizards of the Coast and owner of Magic: The Gathering—was sued by its own shareholders.

The 76-page lawsuit alleges that CEO Chris Cocks, former Wizards president Cynthia Williams, and other executives breached their fiduciary duties by systematically destroying the long-term value of the Magic brand.

The mechanism? They printed too many cards.

Magic launched in 1993. For three decades, it operated on implicit scarcity principles similar to Pokemon. Sets would release, sell through, and go out of print. Cards from older sets appreciated. A mint Black Lotus from 1993 has sold for over $500,000. Players reasonably expected their collections to hold value.

Then Hasbro decided to optimize for quarterly earnings.

Bank of America issued a report in 2022 concluding that Hasbro was "overproducing Magic cards, which have propped up Hasbro's recent results but are destroying the long-term value of the brand."

The company flooded the market anyway. Standard sets, supplemental sets, Secret Lair drops, Universe Beyond crossovers, collector boosters, set boosters, draft boosters, commander decks, premium reprints. The release calendar became so crowded that players coined the term "product fatigue."

When shareholders raised concerns during earnings calls, executives allegedly issued "materially false and misleading" statements about sustainability.

The most damning episode involves Magic's 30th Anniversary Edition.

In October 2022, Wizards announced a $999 product celebrating Magic's 30th birthday. The set contained proxy cards—not tournament legal—that replicated vintage designs. The community reaction was brutal.

Less than an hour after the set went on sale, Wizards tweeted that "sale has concluded, and the product is currently unavailable for purchase." The implication: demand was so overwhelming they'd sold out instantly.

According to the lawsuit, this was manufactured perception. Former employees testified that management had planned to "pause" sales if negative reception threatened launch optics. The company had only sold a portion of printed inventory.

Some of those unsold $1,000 boxes were later discovered in a Texas landfill.

Think about that. A company that owns a 30-year-old brand built on collectible scarcity printed a premium product, couldn't sell it, and threw it in the garbage—while simultaneously flooding the market with so many other products that the entire brand's premium was eroding.

The lawsuit alleges Hasbro spent $125 million repurchasing shares at prices "artificially inflated" by overprinting revenue. When subsequent quarters revealed the damage, share prices fell—meaning the company overpaid for its own stock by approximately $55.9 million.

Hasbro destroyed value by abandoning the scarcity that created value.

The company is not alone.

Nike—once the undisputed king of athletic footwear—experienced one of the most striking brand erosions in modern business history between 2017 and 2024. The company reported a 10% drop in sales and a 44% plunge in profit.

What happened? Nike got greedly. It overproduced, ruining its reseller market and street cred.

Nike was forced into a destructive cycle of deep discounting across its direct channels. The company that spent decades building premium pricing power suddenly found itself competing on price. Digital sales plummeted 20% despite billions in investment.

The diagnosis was brutal: pure online customers proved far more price-sensitive than anticipated because online competition had been fought for years via discount campaigns.

In the last six months of 2024 alone, 8 million fewer Americans said they preferred Nike. The brand simply lost touch with culture.

Nike's new CEO acknowledged the damage: "What I've seen is traffic in Nike direct, digital and physical, has softened because we lack newness in product and we're not delivering inspiring stories. The result is we've become far too promotional."

The company made so many Air Force 1s, Dunks, and Air Jordan 1s that they became commonplace and uncool. Stock down 52% since 2021.

Supreme followed a similar trajectory. The streetwear brand built its entire identity on artificial scarcity—limited drops every Thursday, items that sold out in seconds and never returned. Traffic to their website spiked 17,000% after drops.

Then VF Corporation acquired them for over $2 billion and needed sales to ramp up quickly.

As one analyst put it: "The whole premise behind Supreme and other streetwear brands is that the product is hard to get. It's scarce. And scarcity and growth are really oppositional with each other."

VF Corp sold Supreme at a loss last year after revenue dropped 7% and they took a $735 million impairment charge. The brand that perfected scarcity was destroyed by owners who didn't understand it.

Companies can play scarcity the other way, too.

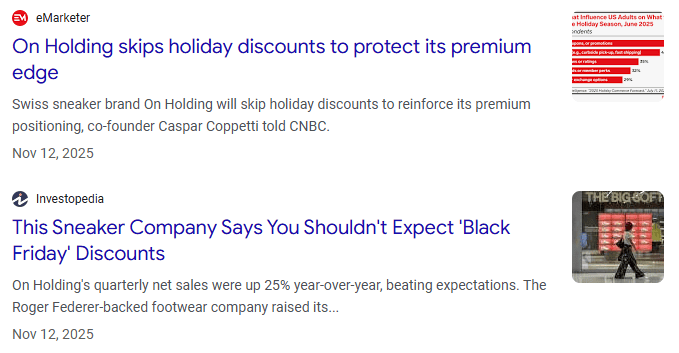

While Nike was destroying brand equity through discounting, a Swiss running shoe company was doing the opposite.

On Running entered the 2020s with momentum and never looked back. Sales jumped 69% in 2022, 47% in 2023, 29% in 2024.

The secret? It never discounts.

On has maintained minimal discounting from the start, using pricing power to fuel brand equity and signal scarcity. Wholesale partners are selected carefully, with strict expectations for presentation, pricing, and environment.

"Our commitment to full price sales is first and foremost, the commitment to build the brand long term," explained Martin Hoffmann, On's co-CEO.

When the broader market turned promotional, On didn't follow. In July 2025, while competitors slashed prices, On quietly raised prices on flagship models by $10. No campaigns, no justifications.

In Q3 2025, On reported revenue of 794 million Swiss francs—beating analyst expectations by 4%. While Nike and Adidas launched Black Friday promotions, On chose to forgo discounts entirely.

The luxury playbook is even more extreme. Hermès has no outlets. Chanel doesn't do Black Friday. Louis Vuitton doesn't put leftover stock in off-price chains.

When they have excess inventory, they destroy it.

Because protecting the brand is more valuable than recouping sunk costs.

The Pokemon Company operates on the same logic without the burning. They simply move on and let scarcity emerge naturally. No reprints, no flooding the market, no destroying the value collectors built over decades.

This brings us to the trust hierarchy.

When you buy gold, you're trusting physics. No one can synthesize it economically (yet). The scarcity is a fact of reality.

When you buy Pokemon cards, you're trusting company behavior. The track record is strong, but a policy change could crater the market tomorrow.

When you buy Nike, you're trusting brand management. That trust proved misplaced.

When you buy Magic, you're trusting Hasbro. And Hasbro demonstrated—with a Texas landfill full of $1,000 proxy cards—exactly what that trust is worth.

This hierarchy maps directly to market behavior.

Gold maintains a $15+ trillion market cap purely on scarcity trust accumulated over millennia.

Pokemon sealed product appreciates because The Pokemon Company has maintained discipline.

Nike collapsed because management violated the scarcity covenant.

Magic's collectible ecosystem is eroding because Hasbro sacrificed long-term value for quarterly numbers.

Which brings us to Bitcoin.

There will only ever be 21 million Bitcoin.

Not because a company promised to stop printing. Not because extraction is physically difficult. Because the supply cap is written into the protocol's code and enforced by a decentralized network that would reject any attempt to change it.

No CEO can print more Bitcoin to make quarterly numbers. No board meeting will conclude they should "monetize the brand" by expanding supply. No shareholders will file a lawsuit because executives abandoned scarcity discipline.

The scarcity isn't a promise. It's the architecture.

Bitcoin's inflation rate—currently under 1% annually after the 2024 halving—is programmatically determined and approaches zero asymptotically. The total supply curve is known and visible to everyone. The current supply is verifiable by anyone running a node.

WisdomTree models three scenarios for money supply growth through 2030. Their base case projects global M2 reaching $134 trillion at 5% annual growth. Hard-money assets are forecast to rise from current levels to 35% of supply.

In that model, Bitcoin captures an increasing share of the hard-asset basket as adoption continues.

Ray Dalio gets it. Larry Fink gets it—BlackRock's iShares Bitcoin Trust became the fastest ETF in history to reach $50 billion in assets.

The thesis isn't complicated: in a world of persistent monetary expansion, scarce assets appreciate relative to the expanding money supply. Bitcoin is the scarcest asset that's also liquid, divisible, portable, and verifiable.

Three forces are converging.

Monetary expansion isn't stopping. The structural dynamics of sovereign debt, entitlement obligations, and political economy point toward continued long-term growth. Dalio cited "unprecedented levels" of indebtedness that make a debt crisis "impossible" to avoid.

Scarcity awareness is exploding. The Pokemon collector who watches sealed product appreciate 400% learns something about supply and demand. The Magic player who watches their collection devalued by overprinting learns about trust. The Nike customer who sees the brand become "always on sale" learns about premiums. These aren't abstract concepts anymore—they're lived experience for millions.

Verifiable scarcity is now possible. Bitcoin demonstrated that cryptographic scarcity could work at scale. That proof of concept has been validated by over a decade of operation and trillions in value.

The statistic that started this analysis made a simple observation: Pokemon boxes outperformed gold, and gold outperformed stocks.

The deeper point is about the nature of value in an era of unlimited money creation.

Hasbro destroyed billions by abandoning scarcity discipline. Nike destroyed billions through discounting. Supreme was gutted by owners who prioritized growth over exclusivity.

The Pokemon Company created billions by maintaining scarcity implicitly. On Running built a premium brand by refusing to play the discount game. Gold has preserved value for 5,000 years because physical scarcity requires no discipline at all.

Bitcoin represents a new category: scarcity that is explicitly designed, cryptographically enforced, and mathematically guaranteed.

For investors thinking about capital preservation in a world of persistent monetary expansion, the lesson from Pokemon robberies, Costco gold frenzies, Magic landfills, and Nike's collapse is consistent:

Scarcity is the asset. Everything else is a promise.

And in a world where the most powerful institutions have repeatedly demonstrated their willingness to break promises when convenient, assets that don't require promises become increasingly valuable.

The only question is how long it takes the market to fully price it in.